One Thousand Visitors

“MOM THERE ARE LIKE A HUNDRED PEOPLE AT MY APARTMENT RIGHT NOW, CAN’T TALK!”

“LIKE THIRTY OF US ARE GOING TO THE BASKETBALL GAME ITS GONNA BE SO FUN.”

“I WANT TO INVITE A THOUSAND PEOPLE TO MY GRADUATION PARTY!"

For years, my parents would say things like, “Alin, you can’t possibly even KNOW a thousand people! You exaggerate so much.” I proved them wrong while I was hospitalized.

I had a lot of visitors when I was hospitalized. A lot.

My program director would come by multiple times a week with candy and gifts. He’d be patient with my parents, who would ask him both medical questions and questions about what was going to happen with residency. I’d wake up after long naps to other ER attendings in my room, just sitting there with my parents— sometimes crying, sometimes laughing, but always there for me.

“I can still be an ER doctor, right?”

My attendings would reply, “Absolutely."

One of my ICU attendings would come by on her days off with People and In Touch magazines. “This will help you get your mind off of all of this.” She would take the time to ask me how I was *really* doing. “I feel fine! I really do!” And then she would stare at me until I said what I *really* wanted to say.

“Chest tubes hurt so much more than I ever thought they would,” I’d admit while looking away.

Priya, my favorite surgical resident, would come by with a bag full of anything she found at CVS Pharmacy on her way home from work every night. She’d be tired as hell after doing a liver resection or a laparotomy for hours. “Today, I got you a neck massager and these scrunchies." She’d lay in bed with me. I would have to force her off because the bed weight alarm would sometimes start beeping. “I don’t care,” she’d say.

Every day, Matt would sneak in muffins and watermelon juice, sit down next to me, and work on his fellowship research with his laptop. Every day, I would tell him that I felt like a burden, that he should go back to fixing ACLs. Every day, he’d tell me to shut up. “You need to stop pushing people away. We all care about you a lot.” I’d roll my eyes and take a sip of my juice.

One of my attendings, known for his stoic demeanor and strict ways, once surprised us all by walking into my room. He stayed and chatted for a long time, in complete shock about my whole situation. When he was leaving, he almost made it to the door before he turned around and looked at me. “Alin, I want to tell you one thing. You have been so strong throughout all of this, it’s been unbelievable … and I just want to say that I would expect absolutely nothing less from one of the best residents I’ve worked with.”

The whole room teared up. But I held my tears back. Instead, I said something along the lines of, “You’re just saying that because I’m dying!”

He shook his head. He walked back to my bed to give me a hug. “You can’t die. We have to clear the waiting room on every shift when you’re back.”

I teared up.

One of my close friends would always bring me breakfast bagels after being on 24-hour-call at the hospital. We had a rule: to not talk about my illness, and to treat me like he would on any other normal day. “When are you coming back to work to admit patients that probably don’t need to be admitted, you dork?” he’d ask. We’d laugh. We’d hug. I appreciated that.

My best friend from medical school flew in from sunny Miami and surprised me. She sat down next to me, and we joked about all of our old times. I sighed. “I miss coming home with you on Thanksgiving breaks."

“You’re gonna still come home with me on every Thanksgiving that you’re off, don’t worry,” she replied.

My girlfriends (aka my sisters) from Los Angeles, Linda and Ateena, even flew in. Ateena would help me with my daily walks around the ICU. She would hold onto my milrinone pump, and I would make jokes about how my life was always in her hands. Linda, who is one of my only friends not in the medical field, walked into the room and asked, “Wait so what's a Cardiac A-ha! diet?”

My brother, cousins and relatives flew in and surprised me as well. “We cannot wait until you’re back in LA,” they’d tell me. My cousin and I would go down the list of everything we were going to do when I was back home on vacation some day.

A former attending of mine, someone I looked up to dearly, once came by with a David Sedaris book and a sketch pad (which really made my day). We laughed so much at my old “intern year” memories. She then showed me a part of her sternotomy scar from a valve replacement years ago. “You’re gonna be in the Zipper Club with me when you get out of here. Pretty cool, right?”

My good friend, a cardiologist, would come by after working long hours (no matter what time it was). He knew that I was always going to ask him all of the super specific cardiology questions that my little brain had thought about all day. “Can we go over the Fick formula? Where exactly is this catheter sitting? How do they check wedge pressures?” One time, we drew out the human heart together on my iPad. I think he knew how nervous and anxious I really was deep inside. He watched me color in the ventricles.

“So, as a cardiologist, not as my friend, but as a cardiologist … am I gonna make it out of here alive?”

“YES! Like no other! You’ll be back at work with a new heart! We’re gonna be going out so soon! First drink’s on you, though, because coming here after being a cardiologist at the hospital all day has really been taking a toll on me.”

I wish I could tell you a story about each visitor who dropped by, but IT WOULD BE LIKE A THOUSAND PAGES OF READING BECAUSE I HAD SOOOOO MANY VISITORS EVERY SINGLE DAY!

Then came New Year’s Eve.

On this particular day, I went to the Cath lab for the umpteenth time only to come back to, literally, ten people in my room. We didn’t have any champagne, but ginger ale worked just as well. One of my friends got me Sour Patch Kids (a real treat when you’re in cardiogenic shock) and I ate the whole bag. "Cheers to 2018. Hope 2019 is a little better than this,” I said, dryly, with SPKs in one hand & a plastic cup of ginger ale in the other.

“It’s gonna be so much better. Hashtag, new year new heart!” One of them said.

“Hashtag, can you guys go out and celebrate FOR me? All of you know that I LOVE this holiday.”

“We know that you love this holiday. That’s why we’re staying."

I fell asleep sometime around 10 or 11pm. I didn’t want to, but I did. Melatonin is a helluva drug.

Anyways, let me tell you the best thing ever right now. Let me tell you that every single person stayed in my room until midnight anyway.

I thought it was kind of weird that they wanted to spend NYE in my hospital room.

Nonetheless…

Thank you.

My dad asked me the next morning, “You remember when you were younger, we’d always hate that you were exaggerating so much? You still always say things like ’There are forty people coming over so I have to get dinner ready!’”

“Yes."

“You were never exaggerating that much. There are a lot of people besides me and your mom who love you. You’re lucky."

Yep. And during that time in my life, I felt extra loved. My support system was actually the reason why I got through what I got through. My “enablers,” as I liked to call them. They were constantly asking the techs to get me blankets, to get me some tissues. My friend once told my nurse, “Her teeth are sensitive. Do you have any toothpaste for sensitive teeth?” (** face-palm ** SO embarrassing, I know.)

They would answer all of my medical questions when I wanted to talk about what was going on. But they would pretend like there was no invasive central line jammed into my little neck on the days that I didn’t want to talk about what was going on.

They would hold the back of my way-too-large gown and walk around the unit with me. When I looked short of breath, they’d say that they’d want to sit down for a second (because they knew that I would never admit that I was short of breath). I knew what they were doing.

They would bring me all of the sweets that I wanted. They’d pretend like it was theirs if my doctor or nurse walked in. Ugh, that Cardiac A-ha! diet…

They would tell me that I looked so good, even when my hemoglobin was 6 and I hadn’t waxed my eyebrows in three weeks. They would sit down and do manicures with me— even the guys who had never had their nails painted before.

They would watch everything on TV with me on the days that I felt down and just didn’t feel like talking. They would pretend like they wanted to watch the 3rd run-through of early 1990s Forensic Files. “We’ll watch these when you’re discharged, too. I’m coming over with popcorn every night."

They would let me vent about how much my F&#(ing arterial line kept F*#$ing up. I rarely complained, but this was one major complaint of mine. “F*$& that line. It’s gonna be out in no time,” they’d say.

They would bring me flowers when they weren’t supposed to. In fact, they would bring me gifts, so many gifts, every day. I couldn’t wear shoes in the hospital, but one time, I told my friend that I badly wanted a pair of Doc Martens. “It’s gonna be the first thing I buy when I’m out of here,” I told him. He came by one day with a neatly wrapped shoebox— Doc Martens. “This is for when you get discharged. You’re gonna wear them on the day you’re out of here.”

“AHHHH! YES!!! Think I can wear these to the OR when I get my transplant?” I asked, as I checked for pitting edema before trying them on.

“You can do whatever the hell you want to do. You’re Alin.”

You see, my support system gave me a lot of hope. They’d give me hope about being out of the hospital “in no time.” We’d talk about being at work again, and how we’d be reminiscing about these terrible (but darkly humorous) times at future get-togethers. They’d tell me that, very soon, I was going to be in California and watching the sunset from my favorite secret spot in Venice Beach. And very soon, I was going to be a New Yorker living the life in the Lower East Side (my dream since I was practically five years old). According to them, I was going to handle all of this so well and so gracefully because "I was Alin” and nothing was going to stop me.

With their validating words and their incessant love for me during this incredibly insane experience, I became a little bit less scared and a little bit stronger each and every day.

I hated it at times, because I would feel like a burden. I would push them away. In fact, I got into arguments with my enablers on some days— I didn’t want them seeing me sick and barely able to walk. I didn’t want them being late to work because of me. But these crazies just kept coming back.

So where I’m at right now in life (still smiling and still determined to kick ass)— this is all thanks to them. So, thank you— all of you— for giving me so much of your beautiful, genuine hope during the absolute worst days of my life.

And to my nurses who were taking care of me (if you’re reading this), I’m sorry for ALL OF THOSE THOUSANDS OF PEOPLE in and out of the unit every day for me.

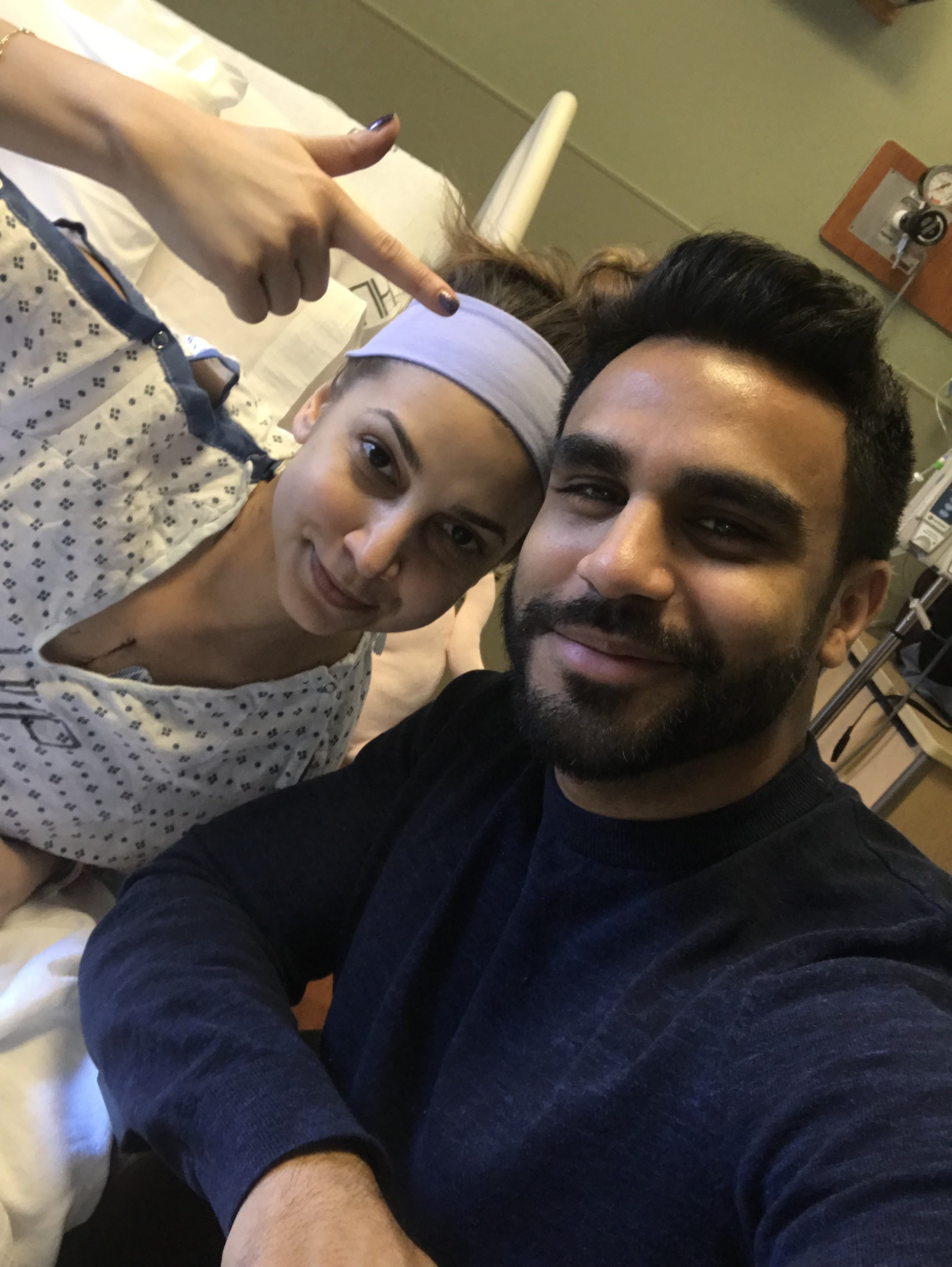

To end this post, here are some photos of me and several of my enablers from when I was hospitalized.